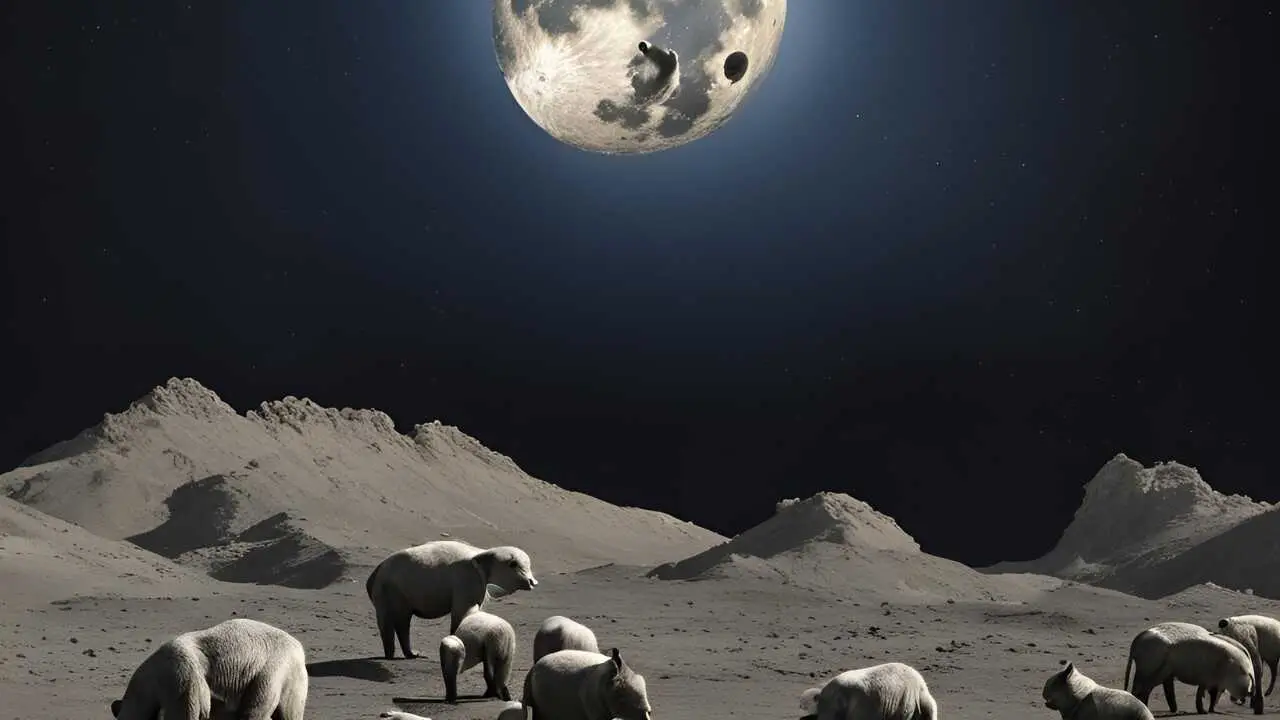

Could the moon soon be home to frozen biological samples of Earth’s endangered creatures? New research suggests that naturally occurring lunar cold spots, some of which haven’t seen sunlight for billions of years, could be the perfect place to preserve these vital samples.

Recent studies estimate there are about 8 million species on Earth, with over 1 million currently facing the threat of extinction. Alarmingly, this number might only scratch the surface, as many species could become extinct before even being identified.

A groundbreaking concept, led by Mary Hagedorn of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, explores the feasibility of creating a biorepository on the moon. This proposed lunar repository would preserve fibroblast cells, which support and connect tissues and organs, from the world’s endangered species. The preservation method, known as cryopreservation, involves deep-freezing cellular material to induce a state of suspended animation, leveraging the moon’s naturally cold environment.

In a recently published article in BioScience, Hagedorn and her team highlight the urgency: “Due to numerous human-induced factors, a significant number of species and ecosystems are facing destabilization and extinction threats, accelerating faster than our efforts to save them in their natural habitats.”

Why the Moon?

If we can’t save the species in their natural habitats, we can at least save their cellular samples through cryopreservation, which could potentially aid future cloning efforts. While we currently have the capability to cryopreserve biological samples on Earth, maintaining the required freezing temperatures is technologically and financially challenging.

The moon’s polar regions, particularly the permanently shadowed craters, offer a unique solution. These craters haven’t seen sunlight for over two billion years, maintaining temperatures below minus 321 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 196 degrees Celsius). Hagedorn and her colleagues propose utilizing these naturally cold areas for passive, long-term cryopreservation storage.

However, this innovative idea comes with significant challenges. The samples must be carefully packaged for space transport and stored to protect them from the moon’s high radiation levels. Additionally, international cooperation and substantial funding are essential to make this project a reality. Despite these hurdles, the team remains optimistic about the feasibility of a lunar biorepository.

Hagedorn and her team have already initiated research using the starry goby (Asterropteryx semipunctata), a carnivorous blue-speckled fish, to develop the necessary protocols for the project.

Whether this ambitious project will succeed remains to be seen, but it offers a glimmer of hope for preserving Earth’s endangered species in an unprecedented way.